TRASHY BUT TRUE: THE STORY OF BLOODKIN

WET TROMBONE BLUES: NEVER MISS A SUNDAY SHOW

“Good luck I think you’re gonna need it

When you’re caught out in the storm

I ain’t no detective don’t come begging to me

When it rains on your trombone”

– Daniel Hutchens, “Wet Trombone Blues”

(Widespread Panic performing their Bloodkin tribute set live at Red Rocks, Sunday, June 27, 2021.)

They say never miss a Sunday show. In fact, it’s one of the most adhered to adages and aphorisms in the jamband lexicon, and one that’s become common slang among true believers who go to see their favorite bands on the proverbial day of rest to grab one last little bit of magic— most often after a long weekend spent listening, experiencing, and communing with freaks and fellow travelers on a shared musical journey for those willing to go the distance— on their way out the door. A night known for leaving it all on the table, it’s become a revered institution unto itself, and one that has become secondhand speak for emotionally-charged performances, consistently producing some of the most revered and heartfelt shows from its many modern day practitioners. A venerated church service for the soul after three nights of revelry and abandon, it’s usually reserved as a space for deeper sets and material— sometimes heavy in nature, sometimes ecstatic, and often a mixture of the two— melding the inherent spirituality of the traditional Sabbath with a sense of exhausted elation after a crazy weekend riding the waves of Friday and Saturday night. In the often obsessive world of their fans looking for rare bust-outs or their own personal “white whales” of setlists, Sunday shows have historically been a moment for reflective jubilation meant to bring a summary end to an otherwise wild and wooly party scene. It doesn’t always work out that way of course, as many bands and fans will attest to, but when it does, and the feeling and vibe is just right, it can be one of the most rewarding experiences in rock and roll.

Although the exact origins of the phrase are a little murky, with many contemporary acts laying claim to its usage, historically speaking, it’s most commonly identified with Southern rock band Widespread Panic and their unwieldy caravan of sonic explorers known lovingly as “Spreadheads”— the traveling circus of pilgrims and psychedelic pranksters who religiously follow their music across the country, laying siege to unsuspecting cities for days at a time with throngs of imbibed hippies and hangers-on in search of a little musical transcendence. Updated and adopted countless times over the years by succeeding generations of improv-heavy outfits who thrive on rewarding their most fervent and diehard fans with unique, one-of-a-kind shows, few bands outside of other likeminded acts like the Grateful Dead and Phish have been able to successfully codify it as part of their audience lingo as the jamband juggernaut from Athens, Georgia. Known for legendary three-night runs at places like Oak Mountain Amphitheatre in Pelham, Alabama, the Fox Theatre in Atlanta, Georgia, and Red Rocks Amphitheatre in Morrison, Colorado, their Sunday shows have fallen into contemporary music lore as not-to-be-missed experiences among hardcore aficionados, with the group consistently managing to turn the celebrated day into a showcase performance space for both themselves and their fanbase.

Which is one of the many reasons I, and many others, didn’t want to miss their Sunday show at Red Rocks this past summer on June 27th. As part of their first run of concerts back in action after over a year of disease, death and lockdowns due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and one of the first major rock bands to hold a large concert of any kind at full capacity in the once-hopeful days of declining caseloads and mass vaccinations, it seemed like a great opportunity to finally shake off the collective cobwebs we had all accrued over the preceding months of fear and fatigue from a once-in-a-generation global health crisis. Having experienced a season of loss like no other in recent memory, both private and public, few things sounded as enticing as spending an evening at the natural wonder that is America’s greatest outdoor concert venue with one of America’s greatest rock and roll bands. Guaranteed to be a loaded event given the circumstances leading up to the concert, and the anxiety-inducing thought of being around a large group of strangers for the first time since March 2020— and still unsure how safe it might be to attend with or without vaccines— there was another, even heavier air hanging around both band and audience, due to the recent loss of founding drummer Todd Nance in August of 2020, after several years away from the band, followed by the untimely death of longtime collaborator and friend Daniel Hutchens from the group Bloodkin on May 9, 2021.

Two integral and beloved figures from the band’s earliest days on the Athens music scene, both of whom would help shape the group’s sound and catalog in unique but different ways, the loss of Nance and Hutchens so close together was a one-two gut punch for a band of brothers who had already said early goodbyes to several key friends, mentors and bandmates over the course of the past two decades. Going back to the passing of founding lead guitarist Michael Houser from pancreatic cancer in 2002, followed by singer-songwriter and brute. co-conspirator Vic Chesnutt in 2009, original keyboardist and Dixie Dregs alum T. (Terry) Lavitz in 2010, Southern surrealist and jamband icon Col. Bruce Hampton in 2017, and Neal Casal— guitarist for Panic affiliate Hardworking Americans— in 2019, the band’s extended family had been dealt a series of personal blows in quick succession. Having persevered through so much grief and adversity over the preceding 20 years, with band members being rotated and replaced by a small cast of close confidants, the twin deaths of Nance and Hutchens was yet another stark reminder of the fragility of life for a group already well-versed in personal and professional tragedy.

With that as the dramatic backdrop against which they’d make their triumphant return to the stage— while also solidifying their place in the venue’s vaunted history with a record 63 sold out shows— it wasn’t lost on those heading to Red Rocks for their three-night run in late-June that a certain layer of sadness and existentialism would permeate the proceedings. Having personally opted out of attending the first two shows on Friday and Saturday due to scheduling, as well as an intimate indoor concert at Denver’s Mission Ballroom that preceding Thursday, for fans that arrived for the full weekend, they would be greeted by a collective sense of joy, relief and camaraderie that only a series of Home Team shows can bring after so much time away from the pulpit. Quickly followed by the realization, brought on by a torrent of cloudy and inclement weather, that this would be a family reunion like no other. Enduring a chilly and rain-drenched first night that saw the band pay homage to Nance with the inclusion of one of his signature tunes, the appropriately titled “Down,” the second evening would see yet another round of storms move through the area, although much less severe, making way for a memorable Saturday night filled with classic Panic tunes from across their catalog, alongside choice covers and a nod to singer-songwriter Vic Chesnutt, with the inclusion of the brute. song “Blight” in the first set, followed by “Degenerate” as part of a two song encore.

Always one to play to both the space and vibe surrounding their shows, paying homage to peers and influences has long been a hallmark of the Panic experience. Covering a wide array of classic tunes alongside the music of hometown or regional heroes like Chesnutt, Hampton, R.E.M., Allman Brothers, and Drivin’ N’ Cryin’— to name a few— there are few groups whose repertoire is as wide and deep as Widespread Panic’s, offering them both the musical and emotional range— through both their own music and the music of others— to truly capture the essence of an evening. Like the Dead before them, they’ve always made a point of honoring early inspirations, as well as artists and songwriters they thought were deserving of wider recognition among the general public, utilizing both the stage and their albums to highlight the work of others who may not have had an opportunity to have their songs heard by such a loyal and attentive audience, many of whom obsess over the historical lineage of the music that makes their favorite bands tick.

And nowhere was that made clearer than on Sunday’s matinee show at Red Rocks, where the band would perform a full opening set of Bloodkin tunes in the rain in honor of the passing of Danny Hutchens, showing off both the profound impact he and the band had had on their catalog over the years, as well as the powerful songwriting prowess of one of America’s most criminally under-recognized rock and roll street poets. Having featured several Bloodkin songs on their albums over the years, especially early on— including the hard-hitting, socio-political anthem “Makes Sense to Me” from their eponymous 1991 sophomore LP; the great “Henry Parsons Died” from 1993’s Everyday; and minor breakout radio hit “Can’t Get High” from 1994’s Ain’t Life Grand— Panic has also regularly included other signature tunes from the band’s catalog in their live sets going back to some of their earliest days on the Athens music scene, and continuing through today. Having fostered an almost symbiotic relationship between the two outfits starting back in the mid-to-late-80s, few modern rock and roll bands have come to be so closely associated with each other on both a personal and professional level as Bloodkin and Widespread Panic.

And nothing brought that message home more than Panic’s opening Sunday set, where the band would run through a ten-song suite of some of Bloodkin’s most beloved tunes, as well as deeper cuts and a brand new track off of their recently released album Black Market Tango, offering up a veritable Danny Hutchens musical highlight reel that showed just how deep the waters and roots actually ran between the two bands. Kicking off the set with the newly intense meta-narrative of “Can’t Get High”— and one of the tracks that would gain Panic some of their first substantial national exposure on both radio and TV— the song’s sobering lyrics about fateful nihilism in the face of heartbreak and despair, and trying to self-medicate, to no avail, with alcohol and drugs, were a poignant entry point into what would be a grand salute to a fallen friend who had struggled with addiction on and off for many years up until his very last days. Coupled with its atmospheric lyrical references to thunder and rain, both of which were in abundance all weekend long, the song— along with the set’s second tune, and one of the very first pieces of music Daniel Hutchens and Eric Carter ever wrote together, the even more-on-the-nose “Wet Trombone Blues,” with its wistful weather-related doldrums— would serve as the opening salvo to a uniquely inspired tribute to Hutchens as only his friends in Widespread Panic could deliver.

Following the introductory two song overture, Panic would proceed to weave a symbolic sonic tapestry throughout the rest of the concert’s first half, playing songs from throughout Bloodkin’s catalog that would touch on personal and existential themes that had proven over time to be far more autobiographical in nature than Hutchens’ intensely literary bent may have initially made them out to be. From a pointed and self-referential “Henry Parsons Died,” to the gritty drugged-out darkness of “Quarter Tank of Gasoline,” the anti-fame anthem of “Success Yourself,” and a new, revelatory song called “Trashy,” there was more than enough metaphorical and literal meaning in the air to bring home the many heavy messages hidden in plain sight in the music. And few bands were as well-equipped to handle that heavy load, in terms of both presentation and delivery, than Bloodkin’s fellow Athenians. As a loose collective who had been through so much together over the preceding 30 plus years— from the ups and downs of a life lived in rock and roll, to the negative effects of drug and alcohol addiction, and the sublime highs of connecting with people through art and music— there have been few acts that could stand so tall in such a moment of sorrow and discontent and still bring a sense of joy to those there to witness it. It was a profound moment, and yet one that managed to shine through the gloom, disease and ever-present cloud cover in glorious fashion. Rain be damned.

So just how did this roving group of musical misfits come to have such a strong bond and working relationship to warrant a moving homage on such a grand scale? It’s a long and complicated story, filled with wild intersections of both art and artists, but what follows next is an attempt to place both the bands and their shared history together in a larger context, coupled with interviews, written tributes, pictures, and video footage from those that were a part of it, in an effort to answer a question many of their fans have asked over the years in terms of their shared songs and stories and the overlap between the two: Just who do they belong to exactly anyway?

As it turns out, it’s an inquiry that’s much easier to ask than answer, and just may surprise some people to learn that its bloodline and family tree runs much deeper than most could ever imagine, particularly when it comes to the music and lyricism of Daniel Hutchens and his brother from another mother, guitarist and Bloodkin co-founder Eric Carter.

From West Virginia and Widespread Panic, to the Velvet Underground and beyond, it’s a story about a place, time, group of people, and a particular communal vibe that would set Southern music on fire while no one— and everyone— was listening, carving a unique set of career paths and crossroads that would resonate deeply for over three decades, through both success and failure, and will surely be celebrated for years to come.

It’s partially the story of Athens, Georgia. But more importantly, it’s the story of Bloodkin. As a band, an idea, an ethos, and an attitude, that would help reshape the landscape of Southern Rock well into the 21st century.

BAPTIZED IN EVERY CREEK IN GEORGIA: THE BIRTH OF BLOODKIN

“Everybody knows his name

They’ve heard about his reputation

They all came to see him buried down in the ground

What you might call a little bit of morbid fascination

What is everybody gonna say?

What is everybody gonna do?

Now that Henry Parsons’ passed away

We got no one to lay our guilt on to”

– Daniel Hutchens, “Henry Parsons Died”

You can’t tell the story of Bloodkin, as both a band and brotherhood, without first telling the story of Daniel Hutchens and Eric Carter. Two lifelong friends and fellow muses, Hutchens and Carter’s roots run deeper than the shafts of a West Virginia coal mine, the fateful result of geographical luck and mutual interests that would find them embarked on a shared musical journey starting from their earliest days of teenage rebellion and rock and roll fandom through the end of Hutchens’ life in 2021. Having first met as children in the small town of Ripley, West Virginia in the early-1970s after Carter’s family had recently relocated there, the pair would quickly bond over shared hobbies and, more importantly, shared records, establishing an early array of influences and inspirations that would go on to inform their sound and aesthetic as Bloodkin. Kindred kid spirits with an affinity for both music and trouble, starting from a very young age Hutchens and Carter formed a working relationship and interpersonal dynamic that would ultimately blossom into a professional career and one of the most quietly revered groups in contemporary Southern underground rock lore. Birthed out of cultural isolation in their hometown and a love of art for art’s sake and existential exploration and excess— for better and for worse— the boys of Bloodkin managed to forge one of the most unique and long-lasting partnerships in modern music, combining a DIY attitude with Stones-y swagger and incredible songwriting that regularly tackled the subtle nuances of the human condition, cloaked in Southern imagery, making them one of the best kept secrets out of a long lineage of criminally obscure bands from both Athens and beyond. Card-carrying members of what David Thomas from Cleveland punk band Pere Ubu would dub the “Brotherhood of the Unknown”— a reference to his group’s initial hope of doing nothing more than releasing a handful of great records very few may ever come across or hear in the name of high art, only to be rediscovered later— Hutchens and Carter’s ambitions never truly progressed past that ironically noble aim, while also managing to escape into the world at large through their friends in Widespread Panic. But before they could do that, they would first have to formulate a musical identity, initially in their hometown of Ripley, followed by a stint in the city of Huntington, West Virginia for college, then briefly Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, and ultimately Athens. Making home recordings in Hutchens’ basement as teenagers, a working methodology that they would continue well into adulthood, and inspired by both the Beat writers and highly literary artists like Bob Dylan, the die was pretty much cast from the moment they first met each other, creating a template for creativity that would pay dividends far down the road.

ERIC CARTER: I met Danny when I was 7 years old. And he was a little bit older than me and I was kind of the new kid that had just moved to town. I’d just moved to Ripley, West Virginia. And I was introduced to him through a friend of his, and at first Danny was like, “Who’s the new kid? Who’s your new friend?” You know how little kids are. But we ended up becoming so close, like pretty quickly, that the other guy kinda got left out. So we had little things in common. We’re like 7, 8, 9 years old— it’s like comic books or baseball cards, junk food or whatever. And I lived on the same street as him, so our parents got to know each other and his parents were a lot older than mine. Danny was the last child. He was the baby. By the time I met Danny his siblings were already gone, so his parents could have been my grandparents’ age. So there was the usual thing of like— especially since he was right down the street— I could go spend the weekend at his house or he’d come to mine to sleep over. Little kids sleep over things. And I think both of us were into music. I mean, at that age, you’re not thinking about “I’m going to start a band,” but music was a big thing to both of us, like sharing records. That was there pretty quick. And Danny had access to a lot of things, because of the things left behind from his older brother and some siblings. So there was a treasure trove of like old comic books and old records and things like that. And then we get to the age where we’re old enough to like start buying our own records and just finding out what we like, trying to find our voice.

DANNY HUTCHENS (from the liner notes of Bloodkin’s One Long Hustle box set): Eric Carter and I met when we were elementary school brats living on Klondyke Road in Ripley, West Virginia. We fell into a creative partnership very early on, at first centered around writing and drawing comic books together and “telling stories;” then we got fascinated with music. My older sisters had stacks and stacks of 45s lying around our house— stuff that teen girls of those days were prone to listen to, some of which I found pretty cool. I fell in love with the Beatles. “I Saw Her Standing There” and “I Want To Hold Your Hand” were huge favorites— I could sing them all the way through at age six, and can still remember every word— as well as the whole Revolver LP. The Monkees, too: “Last Train To Clarksville” and “I’m Not Your Steppin’ Stone” were frequent plays….I spent a great portion of my childhood on my bedroom floor, hunched over a little forest green toy record player, entranced by those great sugary pop hooks wafting off the vinyl….I remember for my birthday one year I asked for a Beatles record and my sister gave me Sgt. Pepper’s. At first I saw the Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club band on the cover and was upset, thought it wasn’t the Beatles…but that record really infected me. Countless hours listening while staring at the lyrics on the back cover, with those great colorful pictures of the band on the fold-out. After awhile my dad’s country collection started sneaking into my playlist, particularly his Johnny Cash records. \\ When I was about 11, Eric’s family moved to Ravenswood, another small town about 15 miles down the interstate from Ripley. Their new house was on Skull Run Road, which Eric and I both thought sounded really cool. He and I stayed in touch and our friendship got stronger, as well as our mutual obsession with music. Eric became the antenna— he seemed to have a nose for the best music, and he would scout it out, discover it, then turn me on to it…first Elton John (for a few years I wanted to be Bernie Taupin, a lyricist who didn’t actually play an instrument)…and then, monumentally, the Rolling Stones and Bob Dylan. When I started listening to their records, that’s when my “fascination” became something a little more serious, a little more irreversible. They kicked down the doors to more discoveries: Gram Parsons and Emmylou Harris, John Lee Hooker, Muddy Waters, Robert Johnson and all the great old blues guys.

ERIC CARTER: I remember one day I came home from school, I think I was 12, and I’d seen one of those little film strips in a music class, and this one was focusing on music from the ’60s. And there was a little segment about Bob Dylan there, and for some reason I just really dug it. And when I got home from school, I ran into the house and asked my mom and said, “Mom, do you have any Bob Die-lon records?” And she said, “It’s Dylan. And I think I do.” And she went to the little attic— she didn’t have a huge record collection, but they had their things— and she pulled out this copy of Bringing It All Back Home. And I took it to my room and put it on and I was just like, man, I gotta call Danny. I gotta call Danny and tell him about this guy. And, like I said, he was a little older, and at that point he was probably starting getting into writing and maybe just learning guitar a little bit. And my first thing was drums, and that probably didn’t come until maybe I was 14. But the Bob Dylan thing when I was 12 years old was huge. And we were already into things before that, like I’d already been listening to the Rolling Stones ‘cause my mom had Hot Rocks on eight track when I was a little kid— I guess that’s where all kids get their music from. Where else they’re going to hear it, you know? My mom had a lot of old Motown, and of course the Beatles and the Rolling Stones. But she also had Barbara Streisand’s Greatest Hits and Barry Manilow and Seals and Croft. There was some Elvis thrown in there and my dad had some of the country stuff I came to appreciate more later. So, all that stuff gets embedded in you so early, and you get through the phase where you’re trying to sound like Bob Dylan. It’s like, let’s try to write lyrics like Blonde on Blonde. You’re trying to play guitar like somebody and that’s how you learn. And hopefully you keep doing that enough, and the goal is to develop your own thing. But there were no bands where we grew up. It was a really small town kind of in the country. We were never going to get a band together here or anything like that, but what we did was we spent a lot of time in each other’s bedrooms just playing, playing with our little tape recorders. Danny was a lot more into that. I think at his house there was a lot more leeway to do stuff like that, ‘cause he was kinda a mama’s boy, and there was more room and there was a basement there, so he can make a lot more noise. And his mom was very forgiving of us, just like staying up until four in the morning and just doing our thing. We didn’t really do that so much at my house.

DANNY HUTCHENS (from the liner notes to the One Long Hustle box set): At around age 13, I started strumming my dad’s old Kraftsman guitar, and Eric started thrashing around on a drum kit owned by his neighbor, Johnny Lynch, who played in a country cover band called “Johnny Lynch and the Lynch Mob.” Mr. Lynch had a big rec room/storage space, a building separate from his house out in the yard, where he kept his drum kit and a big old-fashioned record player/radio cabinet that was like a big end table or something. Eric and I held our first “band practices” in that little space, and before long Eric switched over from drums to guitar as his main instrument. He had been a good drummer, capable of a nice John Bonham impersonation.

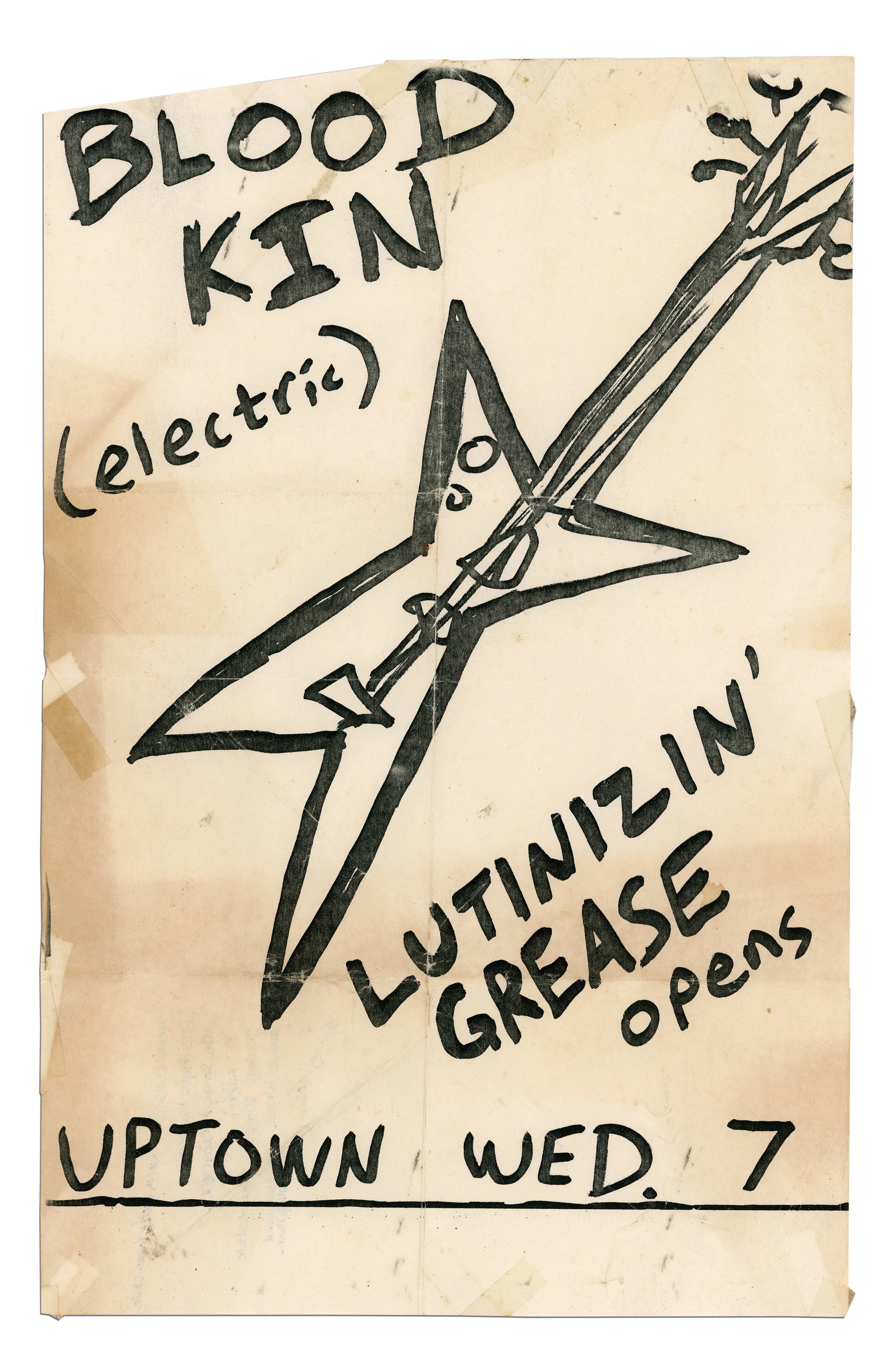

(Early flyer for a performance by The Wreck featuring “Live Original Music And Decadence” at the Monarch Cafe in Huntington, West Virginia. Courtesy of Eric Carter.)

Having found common ground in the sounds and sanctity of each others’ homes and record collections over the course of junior high and high school, despite having begun their first forays into their own music creation by practicing together and recording work tapes— inspired in part by the musings of Jack Kerouac and Neal Cassidy— it wasn’t until after leaving Ripley in the early-1980s to briefly go to college in Huntington that the focus of their lives would really start to take shape in any meaningful way. Having followed each other there to attend Marshall University, it was in Huntington that they would not only form their first proper band, prophetically named The Wreck, but also get a taste of freedom away from their small hometown that would later blossom in Athens. As the place where they would find what Hutchens would call the “perfect setting for our shady little rock n roll fantasy to start coming to life,” although they were initially enamored of what the university town had to offer, it would prove less appealing when it came to actually getting their music heard outside of a small group of likeminded musicians, friends and audiences who would form their sphere of influence away from school and their occasional studying. But it was also a place where some of their biggest and newest musical influences would first start to make themselves known as their listening habits matured, picking up on bands from the classic New York City punk scene, as well as progenitors like the Velvet Underground, and even newer contemporary acts like R.E.M. and the Replacements, as points of inquiry and departure who would go on to inform Hutchens’ own songwriting through their combination of symbolist poetry, noir-ish realism, street attitude, and blasts of manic three-chord energy. It was a heady brew, and a coming of age/rite of passage, and one that would ultimately see the twin flames get their first real taste of a life in music— as well as professional disappointment— while honing their craft, but also— along with a small coterie of friends— want to make their way out of Huntington and towards another small Southern city 433 miles away that was quickly making a name for itself as the new mecca for underground rock and roll in America. As a town that would put a premium on original music in ways that Huntington did not, despite its own massive share of bar bands, Athens was an ideal landing place where they would not just grow, but thrive, immediately making a splash on the local scene and making connections with other artists and musicians who would continue to be a part of their lives and orbit for decades to come. Chief among them being another young band of upstarts known as Widespread Panic, as well as musician/producer David Barbe from the band Bar-B-Q Killers, and later Mercyland and the Bob Mould-fronted power trio Sugar. All of whom would go on to help shape and remake Southern Rock for a new generation away from the towering shadows of “classic” bands of the genre like the Allman Brothers, Lynyrd Skynyrd, and Marshall Tucker Band, among others, while also counting them among their many inspirations in a post-punk and post-new wave world. It was also where Hutchens and Carter would first introduce the band and rotating cast of characters known as Bloodkin to the world after leaving The Wreck behind in West Virginia. Doing a brief stopover in Myrtle Beach to live with Carter’s mom while they figured out their next move, they would eventually arrive in the Classic City in the summer of 1986 and immediately start scoping out the local music scene.

ERIC CARTER: You know, that Southern thing is kind of funny. I mean, me and Danny, we’ve lived in Georgia since 1986. And every time we moved, we moved further south. But I’m always like, technically we grew up in West Virginia, so there’s a different kind of— I don’t know how to describe West Virginia— but it’s a different vibe and it’s not quite the south, but it’s definitely got some of those elements, and it’s not the north. It’s just this weird place in the middle. It’s a different kind of vibe and I still can’t put my finger on what it is exactly. I can feel it, but I can’t explain it.

DANNY HUTCHENS (from the liner notes to the One Long Hustle box set): Huntington was not generally receptive to new music— it was a college town and a crossroads through which many creative types passed, but it was also somehow very conservative— you pretty much had to play in a top 40 cover band to get any regular gigs. However, several local bands started up something called “Original Live Music” night at a club called the Monarch Cafe. The idea was that every Wednesday night, three or four bands would split the bill, playing about 45 minutes apiece, and the rule was that no cover songs were allowed. Original Live Music started to create a little buzz, drawing about 200 people to the club each Wednesday night (which was unheard of for Huntington), and even receiving a few write-ups in the local newspapers. As I remember, the main bands involved were: The Wreck, Ethical Committee, Street Urchin, and New Toys (from Ashland, Kentucky). \\ It all seemed promising. Several of the bands chipped in to rent a very cool rehearsal space downtown on 4th Avenue, up on the second floor of some building in the business district. Enormous windows up at the front of the space, overlooking the traffic on the main drag right below. A fairly nice P.A. and recording set-up. A few “record company weasel” types even came sniffing around; I remember one guy from some major label coming up to the rehearsal space and lecturing all of us about “professionalism” and “appearances”: what clothes to wear onstage, how to cut hair, etc. We all stood around swigging beer and laughing at him.

ERIC CARTER: And you don’t know this [at the time]— people from the outside can see this— but when you’re the one in it, you don’t really think of it like this, but it’s another hindsight thing. It’s like people since then have said, “Man, when you and Danny showed up, it was like you were fully formed. You already had all these songs.” And it’s like “who are these new kids,” you know? So we kind of got into what little original music scene there was and we kind of fell in with some of that crew, and we got our first little band there. And this one place that we used to hang out at, there were a bunch of different original bands. So we all kind of came to this club and said, “How about you give us one night a week and we can all do a little set of just our stuff.” ‘Cause the only thing around there were like cover bands— like heavy metal cover bands or pop covers. So they actually let us do that. And I remember the first time we played, me and Daniel were so excited because this is all we wanted to do is just find a place to be able to play our own songs and have a little band. And I remember me and Daniel were so excited after the first time, and this other guy, this jaded old Huntington musician, he was like, “You guys don’t know shit yet, man. You don’t know what you’re getting into.” And he was probably like 25 at the time. He said, “I’ve been to New York City. You don’t know what the fuck this is.” And it’s like, man, we just want to fucking play our shit dude, lighten up. But Huntington was kind of downbeat economically and things like that. And a lot of the people that we met were a little older and had already been there or else that’s where they were from. So a lot of those people started moving. And that little thing that was burning, that little ember, it kind of cooled off. We’d already heard about Athens a little bit. There was another buddy of mine that lived in Huntington, and he was a huge R.E.M. fan, and he was looking for a place to move and Athens was something that kept coming up. So, it’s like, let’s give it a shot. At that time, that’s when the college music radio thing was kind of taking off. That was becoming a thing, I guess, the format. So you were starting to hear more of that kind of music, shit you weren’t gonna hear on the radio until you go to the left of the dial, as the song goes. So Athens just happened to be the one. There’s probably several other college towns that were probably just like that, that probably had the same kind of thing brewing, but this is the one where we ended up.

DANNY HUTCHENS (from the liner notes to the One Long Hustle box set): We wound up in Athens mainly by chance— we’d heard about the music scene just like everyone else in America, and we thought we’d move there and give it a try. We never thought we’d wind up staying twenty-plus years. But Athens delivered on all the things Huntington hadn’t, and then some. To this day, there’s not a better place in the world to start up a rock and roll band. I’m not sure exactly what makes it such a great place for music— I don’t think anyone’s ever really been sure. That’s part of the magic; you can’t put your finger on it. \\ One thing that helped was that rent in Athens was extremely cheap back in the ‘80s. You could work a part-time day job and pay the rent, feed yourself, and still have money left over, and have all this precious time to spend on your band, your songs, your canvases, whatever you were into— for Eric and me it was Heaven. And more than anything else, by the time we hit Athens there were venues that booked original music— several of them. In earlier days that wasn’t the case— bands like the B-52s started off playing house parties because there weren’t really live stages in town— but that had definitely changed by the time we got here. There were decent stages with decent P.A. systems all over town, and tons of excellent bands taking advantage of those stages. Hell, sometimes the bands even got paid.

ERIC CARTER: When me and Danny first got here in the summer of 1986, it was like in July. And back in those days, in the summertime, it was really a ghost town. It was very quiet. Which was probably good because that gave us time to get settled a little bit, find a little place, and start going around, to eventually meeting people. I think all that stuff probably happened pretty fast. We met a bunch of people that were from this whole crew that had all come up from Savannah. It was like Britt [West] and Samantha Woods, and that was the Perforated Squares, which later became White Buffalo. Danny and I had moved into this little duplex and on the other side of us was Alberto Salazarte’s brother. And Alberto used to play with Perforated Squares. And Alberto’s brother called [Alberto] and said, “Man, you got to come over here. There’s these two guys that just moved in and all they do is fucking play guitars.” It’s like, you gotta come over and meet them. So, start meeting people like that and sort of getting into a little scene, and basically Britt West became our bass player and he didn’t even play bass, but he’s like, “Yeah, I’ll play with you guys.” And Alberto started playing drums for us. So we were basically already sharing a band. They already had their band house, like where they practiced and stuff, so that was our first little group of people. And then we started meeting people on the fringes of that, like their whole little gang. I’m not sure exactly when Widespread Panic got going or when they started doing their Monday nights at the Uptown [Lounge], like for a dollar. And I saw a lot of those because that was one of the only places I could drink and just go out and meet people. I could drink there and it was pretty casual in those days. When we first got here the 40 Watt was on Broad Street and the Uptown I think was on Washington Street. And those were really, as far as I knew, like the only two places going for that kind of original sort of stuff. I think there were some other little things happening, like maybe more college bars, kind of frat bars or whatever. But at that time, those two were kind of the thing for original kind of stuff. I remember the first show that me and Danny went to here in town— I think it was at the 40 Watt on Broad Street— and I believe it was Dreams So Real opening for Porn Orchard. Which, if you know those bands, is a really odd billing, but I think then it was just like, they probably all knew each other. It was like, “Hey, can we open for you guys? And next time you can open for us.” That kind of thing. And the bars closed earlier in those days, like they closed at midnight. So that’s why there was a lot more house parties and things like that back in those days. I guess some bands had probably gotten into the frat circuit. I think Panic did a lot of that. And I think they made some pretty— by the standards of that time— good money doing that kind of stuff. We never quite got into the frat circuit. Well, we did some over the years, but that wasn’t a regular thing. I think a lot of bands, if they could just get a couple of gigs like that it’s like, “we can get a bunch of new equipment now,” you know, shit like that.

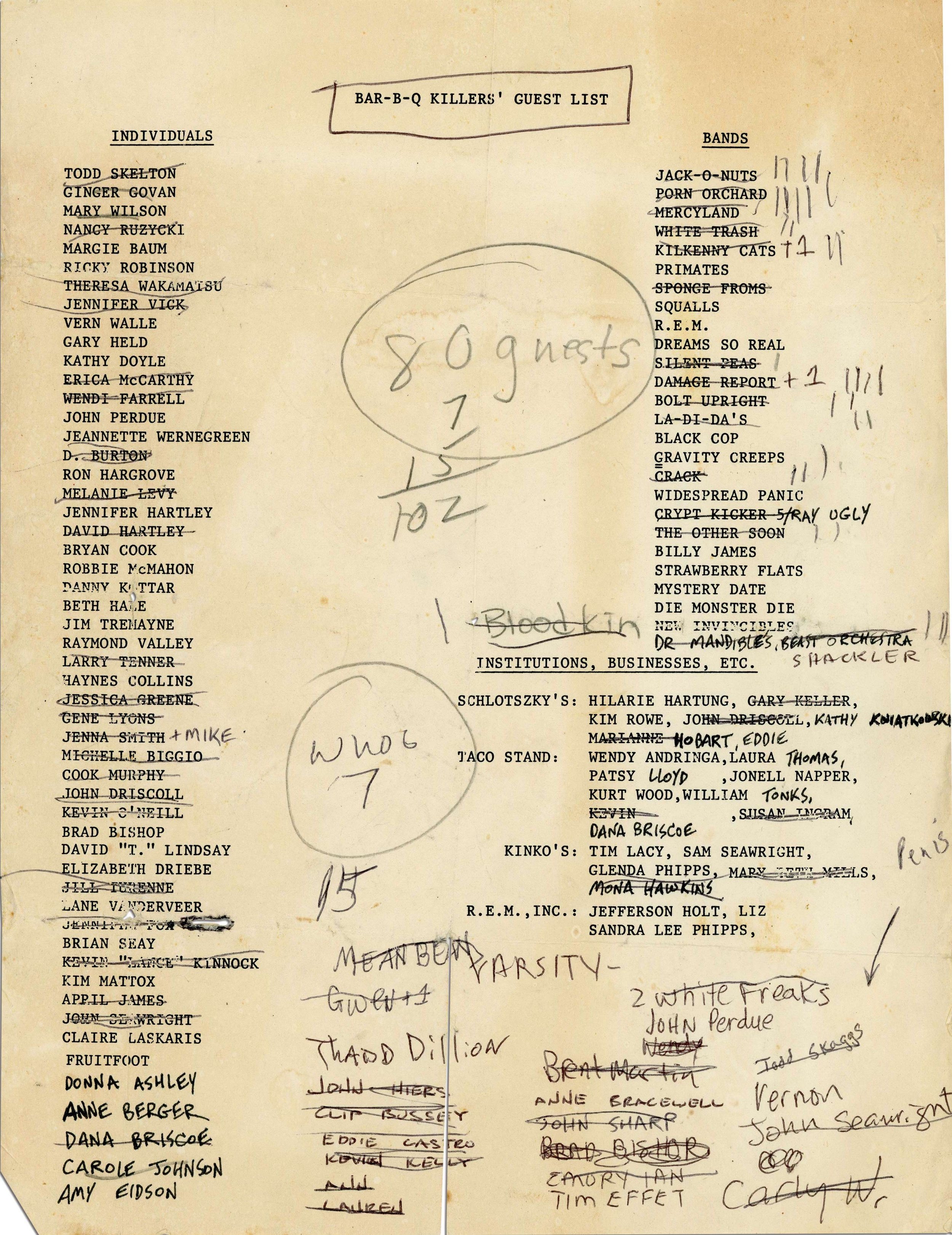

DANNY HUTCHENS (from the liner notes to the One Long Hustle box set): The first show Eric and I attended in Athens was at the old 40 Watt in what I think was its third incarnation, on Broad Street: Porn Orchard opening for Dreams So Real (in retrospect an unusual pairing). The first few years in town we saw all these bands on little local stages: R.E.M. (one of their first “unannounced” shows), Mercyland, Bar-B-Q Killers, White Trash, Kilkenny Cats, Flat Duo Jets, Crack, Billy James, Todd McBride (who went on to form Dashboard Saviors with two more Huntington exports, Mike Gibson and John Crist), Vic Chesnutt, Widespread Panic, etc. It was a blast. It was an education. Attending all those shows those first few years was my coming of age as a songwriter. Hearing all that wildly creative, exciting, brilliantly beautiful and brilliantly ugly music cracked my skull wide open, let all the colors pour in and mix around and form a few new colors and then start pouring back out…for a while it was truly hard for me to keep up with myself, I was filling so many notebooks with new songs and poems. \\ The first official Bloodkin show was sometime in the fall of 1986 at the Uptown Lounge. I’d taken the band name from a short story by William Goyen called The Faces Of Blood Kindred. Eric and I finally came to an agreement on the name at an overnight party over on West Lake Drive. On bass and drums were Britt West and Alberto Salazarte, respectively, who also played in Perforated Squares, and about six months later would go on to form the funk rock outfit White Buffalo. But for a while they helped us out. Those earliest Bloodkin shows, to be honest, were more an excuse for a party than anything else. We always had tons of fun, and with Britt and Alberto’s funk-ish sensibilities we always had lots of dancers.

(Danny Hutchens and Eric Carter, circa early-1990s.)

Having started to dip their toes into the local scene upon their arrival, with a particular affinity shown for the crowds and bands at the Uptown Lounge, it wasn’t too long before Hutchens and Carter would begin to widen their circle of friends and acquaintances to include an entourage of fellow musicians, some of whom, including the members of Widespread Panic, as well as musician/producer David Barbe, would become lifelong collaborators both on the road and in the studio. Yet despite being newly-minted interlopers on a scene that could be somewhat territorial, especially when it came to out-of-towners, the duo quickly established themselves as a force to be reckoned with, in terms of both chops and attitude, highlighting their unique familial bond from childhood that would soon start to pay dividends when it came to their newly emerging songcraft. Equally inspired by the lyricism, musicianship and debauchery of the Replacements and the Stones, and landing somewhere in between, their earliest entries into the Bloodkin catalog were at turns raucous, smart, soulful, bluesy and punk-as-fuck, with a harder edge to them than would make itself known later in their career as they progressed as a band, yet still distanced from the current crop of art rock emanating from places like the 40 Watt. But for those just meeting them in the Athens scene, they were hard to miss, let alone forget— as both people and a band— with a reputation for hard partying and fledgling rock star attitude that often preceded them.

DAVE SCHOOLS (from Widespread Panic): I can’t put a year on it, but I can put a place on it. And the place was a sort of rehearsal bin that we all rented. It was in a big complex of buildings just off of downtown— you could see the back of the art school at UGA. There was a huge bar called Buckhead Beach— I don’t even remember if it was still going, but the sign was still there. And there was a bunch of lofts and bins, and we had a rehearsal bin and we shared it with a band called White Buffalo. And we did a lot of gigs with White Buffalo, and at some point, Danny and Eric showed up, and they became part of our crew and they began sharing that space with us. There were a lot of shows going down at the Uptown Lounge at that time, which was sort of the little off-to-the-side competition with the 40 Watt, as far as like national nightclubs or local nightclubs that hosted national acts. The Uptown had a lot of local acts, but I can remember Black Flag coming there and playing a couple of nights, Camper Van Beethoven. It was a really cool place. We played a lot of gigs and I worked there. And so in the course of working there, I saw— I don’t know if it was the first Bloodkin show there, or the first one I saw, I don’t think it matters— but it was unbelievable. It was just like preaching straight out from the rock and roll gospel. And those guys showed up in town from wherever they came from in West Virginia, literally looking like the love children of Keith Richards and Steven Tyler. Like Aerosmith and the Stones blew through town and left a little remnant of their DNA and they came striding down to Athens, Georgia as Danny Hutchens and Eric Carter. And you know, like us, it was an anomaly from what was happening in the town at the time. This is the mid-80s and Athens was so hip. It was so hip that when I arrived there in the fall of 1983 to go to college, they had already discounted R.E.M. as having sold out in 1983. So you have these bands, like the Bar-B-Q Killers and a lot of like really artistic noise-icians, really. So here’s Widespread Panic playing a lot of covers and slowly learning to write their original songs, and White Buffalo with Samantha Woods singing, playing a lot of like soul and funk. And then here comes Danny, and here comes Eric, and it’s just like they came slicing through the scene.

DAVID BARBE (producer/musician; Bar-B-Q Killers, Mercyland, Sugar): Danny and Eric moved to town in July of 86. And when they arrived in Athens, I think I was in Amarillo, Texas for about a week, as Eric told me recently, when they moved. And I was like, “oh yeah, I remember that week.” I was in Texas and I was just driving around the country, distributing cassettes out of the back of my truck with my girlfriend and did it for about six weeks until I ran out of money in Minneapolis. We just made like a big circle and got from Athens to San Diego, down in Mexico, up to Seattle and across to Minneapolis. And it was like, okay, we have to go to Athens now, we’re broke. But we would sleep in the truck and stuff. But I got back, and later that summer I went to a show at the Uptown Lounge, and might have even played it. It could have been a Mercyland show. But after the show, I went to a party that’s at this house, and didn’t meet them, but I heard about them. And there was this girl, Kim, and then this guy, Tim— Kim and Tim, who had just moved from West Virginia with Danny and Eric. And Kim and Tim were an item. But those were the two people I met, and they’re talking about how they want their friends to come back so I can meet them, because their friends are great songwriters and a great band. Now, I’m also 22, and I fancy myself to be a great songwriter in a great rock and roll band. And I’m from Athens, and I just played this show. And you know how dudes that age are, we’re all that way— Danny and Eric were that way. And just like the attitude that they had, you know, people were like “who do these guys think they are?,” because they just owned the place when they came in. But so Kim and Tim are telling me about these guys, and what’s their whole thing. And I was like, “well, cool, I’d like to meet them,” because I would. It was like, cool, more people moving to Athens making music. But it was the kind of the early period of people coming to Athens just to make music. The rest of us had all come to Athens to go to college and realized, oh fuck, you can be in a band here, this is cool. So suddenly it’s like, ooh— this is different, this is weird. But she was telling me— they both were like— “these guys are like Mick and Keith.” Now, I am every bit the Rolling Stones fan that Eric and Danny are. I love all the same shit those guys do. And so when somebody tells you that some other dudes are that, it’s just like, “yeah, and my son, when he plays basketball, he is like Michael Jordan.” And it’s like, okay, “she looks just like a young Elizabeth Taylor except much more beautiful.” It’s like, okay….sure. I’m getting a beer. And so they were really talked up, but I came away from that evening, like not necessarily doubting Thomas, like I need to stick my fingers in the wounds of these two guys and see if they actually are any good or not, but I was aware that their friends took what they did very seriously. So I remember that more than I remember actually meeting them the first time.

(Early Bloodkin flyer for a show at the Uptown Lounge, circa mid-to-late-1980s. Used with permission from Chunklet Industries, courtesy of the Dan Matthews collection from the book Plus 1 Athens.)

Both Barbe and Schools would go on to become lifelong friends with the Bloodkin boys after meeting them, but even more importantly, would each in their own way and capacity help to further Hutchens and Carter’s musical careers, with Barbe eventually taking the role of their most trusted producer and studio confidante— helping churn out multiple albums for both Bloodkin and Hutchens’ solo work— and Schools, with the help of his bandmates, helping to elevate some of their earliest songs into staples of Widespread Panic’s setlists and albums, as well as getting them their first record deal. As a band that was still formulating their own style and sound, for the Panic crew, Bloodkin would prove to be not just brothers-in-arms, but an incredible source of inspiration that would carry over for decades to come, helping to inform their own songwriting, with Hutchens’ vast collection of poetry notebooks and song sketches catching the eyes and ears of the group very early on and eventually translating into some of their most covered, and beloved, tunes. But beyond that, Bloodkin would also go on to become a part of a wider ecosystem of bands that would not just perform alongside Panic at shows, but also hold late-night after-parties at venues around the Southeast, hearkening back to some of their earliest encounters when both outfits would play house party shows in Athens after bars closed down at midnight or as part of weekend gatherings for both students and locals. Part of an Athens tradition that stretched back to the genesis of the B-52s in the late-1970s, and the many off-campus parties that would eventually give birth to the new crop of post-punk and college rock bands of the 1980s, it was during some of those initial late-night soirées that the bond between Bloodkin and Panic would be solidified in ways neither could have possibly imagined.

DAVE SCHOOLS: Well, proximity is a big deal. It’s a small town. It was inexpensive to live there, especially back in the eighties. All these big houses that weren’t sorority or fraternity houses, these big old Southern homes. Now they’re all like real estate agencies and lawyers’ offices and stuff. But back then they were sort of in disrepair, but it was a great opportunity for like an entire band to be able to live in a big house, and everybody could have their own room, and everybody could rehearse. And so there was a big house party scene, especially on Saturdays. Because for the longest time alcohol sales and bars shut down at midnight on Saturday because it wasn’t Saturday anymore. It was the Lord’s day, Sunday. You had all these bands living in these houses, and a place to set up their gear and play, and generally neighbors that didn’t give a shit about noise. And so you had this house party scene. And you can talk to Fred Schneider or Cindy Wilson about it from the B-52s. They’d tell you the same thing. It was like “party at the Rum Jungle house tonight,” or “party at the Pylon house,” or party at some old warehouse, like Stitchcraft. Or Widespread Panic played every Monday at the Uptown— “party at the Widespread Panic house,” until the city councilman that lived down the street got pissed off and called the cops. So that’s one thing.

ERIC CARTER: It’s interesting, back in the early days, they were kind of getting their thing going and trying to find their own voice too. Trying to find their way. At the time, they all lived here, so we all saw each other all the time— this is still in the 80s. We had our first band house on Elizabeth Street, probably in like ’87. And then the next one, it was probably ’88 or ’89, we moved to this place on North Avenue and we had one of our own little weekend backyard parties there. And I think by this point we were getting to know them fairly well, and by this time they were getting pretty popular, they were trending upwards. And we asked them if they wanted to play in our backyard: “We’re going to play, you guys want to come over? We’ve got the PA,” and blah, blah, blah. And they said, “sure.” I don’t think some of their management was too happy about it at the time, ‘cause I think when you’ve got another gig, you don’t want to cross up gigs or whatever. But to us, it was just like, “hey man, you want to come over to our house and fucking play?” I think that was a pretty big moment. Like, they were hanging out in our world, and hanging out in the house. And, I don’t know if it was JB or Todd, or somebody that was hanging out, like went into Danny’s room, and was like, “Holy shit, look at all these fucking notebooks of lyrics!” Just getting to know each other like that. And there might’ve been a period where I would see JB a lot or maybe he happened to go to this particular bar at this particular time. And it’s like, let’s make it a thing. I had a little period with Dave Schools like that. And they were just around a lot more. So they started getting us to open some shows for them here and there.

DANNY HUTCHENS (from the liner notes to the One Long Hustle box set): The North Avenue overnight parties became a semi-regular event, and one weekend we had a big “bonfire” gathering in the back yard with several bands playing, including Widespread Panic— much to the dismay of their manager, Sam Lanier— because they were actually starting to hit it and make real money. This was the very last time they played a house party for free. I remember sitting on the back porch, about five feet to the left of Todd Nance— and I’d seen these guys playing several times before, Monday nights at the Uptown, but this time I really paid attention and I GOT IT. Watching Todd play those drums right beside me, I realized that he was easily as great as any of the rock n roll “greats,” like Charlie Watts or Levon Helm. This was the night Eric and I cemented our friendship with all the Panic guys. Mikey Houser was hanging out in my bedroom, looking through my notebooks, and asking me to sing some of my songs for him. I was hoarse from being up for days on end without sleep— but Mikey still seemed to like the songs. Then Todd came in, too, digging through my notebooks while I sat there stoned on my bare mattress on my bare floor— and I thought to myself, “These guys are okay— they’re as crazy as me and Eric.” It was the beginning of a long friendship.

BAR TABS BUILT FOR DREAMERS: ATHENS, GA OUTSIDE/IN

“The barstools built for dreamers

We’ll fit fine and find

All the world’s dreams have died

But tonight they’re only taking thirsty people

Who’ve been pullin’ on their drinks

From a glass that lies a bar length wide”

– Widespread Panic, “Barstools and Dreamers”

(Bar-B-Q Killers show guest list, circa 1988, feat. Bloodkin, Widespread Panic, R.E.M., Squalls, Dreams So Real, Porn Orchard, Kilkenny Cats, Mercyland, et al. Used with permission from Chunklet Industries, courtesy of the Arthur Johnson collection from the Plus 1 Athens book.)

As a small town filled with big dreamers hoping to catch the next wave of local media attention that had made national names out of acts like R.E.M. and the B-52s in the earlier half of the decade, it wasn’t just a robust music scene built around house parties and shows at the 40 Watt and Uptown Lounge that Hutchens and Carter had stumbled into. In fact, they soon found themselves at the center of another great longstanding Athens tradition, based around a strong professional community of both established and burgeoning artists from across multiple disciplines, who made a point of helping one another and passing along good will and support in what was a multifaceted, yet insular, scene in a predominantly mainstream Southern city ruled by college football and fraternity parties. Always on the lookout for fellow freaks and musicians who were pushing the scene forward in new and unexpected ways, among the cognoscenti in town, Bloodkin would find not just a welcome home, but a network of like-minded individuals and bands who would help keep the creative torch alive for each other in the Classic City. Following a code of conduct and overall vibe that would receive national recognition in the down-home 1987 documentary Athens, GA: Inside/Out— with its friendly snapshots of indie-Americana come to life in north Georgia— there was always a collective sensibility at work in Athens that seemed to prize cooperation and a sense of camaraderie over all else. Of course, as with any other music scene around the world, there were cliques, and friendly (and not so friendly) competitions between bands vying for the public’s attention and a shot at the big time, but for the most part, a general atmosphere of good will and mutual appreciation reigned supreme, even among artists that the public at large may have considered to be at polar ends of the sonic spectrum, in terms of music, presentation, and fanbase. In the end, they were all dipping into the same communal well anyways, and as with any true Southerners at heart, a helping hand and spirit of congenial hospitality were looked upon far more favorably than any bullshit rock star attitudes or petty backstabbing, as you would more than likely run into any perceived foes on a far more regular and uncomfortable basis than in a larger city like Atlanta or Nashville. Lifting each other up as a sign of solidarity, playing in each others bands and on records, hosting shows together, and just hanging around town— and built around deep and long-lasting friendships— it was an ethos that would go on to benefit the worlds of Bloodkin and Widespread Panic in profound ways, and become something of a hallmark of their professional careers together. Challenging each other to write better and better music, and cheering one another along the way, it was an inspiring creative atmosphere to be a part of as a young band trying to make their mark.

DAVID BARBE: Well, that all goes back to R.E.M. You know, R.E.M. was so generous with their knowledge and opportunity, and providing opportunity for others— literally with other bands [offering] their excess bass strings and drumsticks and things— that they just set the tone of how to do your business as a rock band. And they begat the same type of practices that are carried out to this day by Widespread Panic and Drive-By Truckers. And certainly was a big influence on me. And so you see those bands who continue to pay that forward. And then as a result, the next group of people, it’s kind of the same way, because they see that here that’s how we do it. It’s like the music scene in Athens really isn’t a competitive thing. It’s a collaborative thing. And that’s what makes it so different than a lot of other places I’ve spent time, is that in other places it’s like, you winning means I’m losing. And really, that’s just not how it is. Just because you win doesn’t mean I lose. I mean, we can both be successful at something, right? Last time I checked. But music scenes, it’s so territorial, and just not cool. And Athens, it’s never been like that here. Frankly, everybody’s pretty cool. And Panic and the spirit between Panic and Bloodkin exemplifies that for sure.

DAVE SCHOOLS: And the other thing is, and I’ll tell you, David Barbe knows exactly what the hell he’s talking about, because I just wrote a forward for a friend of mine who’s putting a book together about flyers of Athens from like 1967 to 2004. And I’ve told this story before. I’ve told it when I delivered a commencement address for Barbe’s MBUS program, I’ve written about it, and I’ll tell it one more time, and I’ll always tell it— because it speaks not only of Dave Barbe, but how representative he is of the spirit we’re talking about in Athens, Georgia. I was a freshman, I came down from Richmond, Virginia, I threw my shit into my dorm room, and my roommate walked in and immediately saw my flat of Grateful Dead cassette bootleg tapes and soured on me immediately. So I was like, “well, this has got off to a great start.” And I had made some friends across the hall, but I was walking out into the Reed Quad, just sort of wandering around aimlessly, going, “what have I done with this whole college thing?” (Laughs) And this shirtless, almost like afro’d guy, with a little plastic Chiclets necklace, just comes up to me and thrusts his hand out and says, “Hi, my name’s Dave, what’s yours?” And I said, “Well, my name is Dave too.” And he says, “I’m Dave Barbe, I play bass.” And I’m like, “I’m Dave Schools, I play bass.” And we’ve known each other— he introduced me to Arthur Johnson and Laura Carter and David Judd in the Bar-B-Q Killers, and Harry Joyner— and the list goes on. But it is that spirit inherent in somebody thrusting their hand out and taking the initiative to bring an outsider in. Now, Athens might be the toughest town to move to as a band, ‘cause we don’t like that. You don’t come here as a band because Athens is where you make it— with the exception that proves the rule being Patterson and Cooley [of Drive-By Truckers], obviously. But most people got together because they were a bunch of friends and they just wanted to hang out and play music. And so by virtue of it being a small town, people played in all kinds of different bands. You know, this band could be made up of members of three other bands, and it still works that way to this day. And you have these collectives like Elephant 6, and those guys and all of their bands, and that sort of collective thing was what was happening with Widespread Panic and Bloodkin and White Buffalo.

DANNY HUTCHENS: Like I said, for example— the Panic guys, us, Vic. A lot of different bands that we’re just buddies with, you know, like not even necessarily just music, just like hanging out, drinking a beer or whatever. In those days, Athens was an even smaller town, you know? There were a couple places to play. We all went there, we all saw each other at the Uptown Lounge, and at the 40 Watt we all saw each other. It was like going to school. Because if you went to the Uptown Lounge five nights a week, you’d see a lot of the same people there in the crowd, this kind of rotating who was on stage. This included Panic, and sometimes R.E.M. would come in, and sometimes Vic Chesnutt. This was world-class songwriting. This was not fucking around. And to me, I just moved here and it was exactly what I was looking for, because Eric Carter and I had lived in Huntington, West Virginia, where at the time, if you wanted the gig, you had to be in a cover band. They didn’t want to hear any original music. And when we moved to Athens, you were expected to not only write your own stuff, but it better be pretty fucking good. I mean, it was the bar. The bar was very high, even just among, you know, the hundred of us or fifty or however many people were at at the bar each night. Like, “Man, Vic Chesnutt played here last night. R.E.M. play here.” It was real. And then to me that was just kind of daunting for a minute, but then it was like, this is great. It was an education, and it was just so creative, and it was so mutually supportive. It was such a great music community. I can’t overstate it. Having been in other cities since then, little bits of time here and there— I’ve been in Nashville or New York or whatever— it just always seemed to be much more competitive, kind of cutthroat. And Athens, and I think it’s got to still be this way— I mean, I probably don’t have the same perspective because I’m older and I have kids and I don’t go out every night— but I know, if somebody’s amp blows up, people call me and vice versa, you know? I’ll be there. And that’s just how it is. There’s healthy competition amongst everybody to be a better songwriter, but there’s sort of a more friendly, familial vibe, even within the cliques. It’s more like a friendly competition. Like, “Oh man, did you hear that? That’s Vic’s new song. Did you hear that shit?” Really cheering each other on. I mean, for real. But, of course you wanted to show up, and wanted to say, “Hey, this is what I have.”

And it was that same spirit of camaraderie that would eventually lead Panic to cover not just songs from the Bloodkin catalog, but also collaborate with other local musicians like Vic Chesnutt in the group brute., as well as pay homage to early Athens influences like Love Tractor, who the band would name one of their most beloved songs after on their second self-titled album from 1991, affectionately known as Mom’s Kitchen. Their first release on the newly-rebooted Capricorn Records, it was also the same album that Bloodkin, and Danny Hutchens as a songwriter, would make their recording debut on with the inclusion of the now-canonical tune “Makes Sense to Me,” three full years before the world at large would ever get to hear the band itself on a proper album.

But perhaps one of the greatest, and most memorable, expressions of the communal Athens vibe would start even earlier than that in 1990 in what would become a multi-year event billed as Bar Tab, in which members of the Athens music community would come together in support of one another— and usually a charitable cause— but also as a way to pay wayward bar tabs in need of settling amongst the participants. Lasting from 1990 to 1995, with other permutations taking place periodically since then, the Bar Tab shows were a chance for friends and musical peers to hang out, play with each other, debut new songs and projects, and generally just jam with each other and have a good time. A hallmark of the early days of both Bloodkin and Widespread Panic when they were just starting to make their way in the music business and gain new audiences, they were a great example of what made, and has continued to make, Athens such a unique part of Georgia music history, as well as that of America as a whole. Loose, fun, and with plenty of libations to go around for everyone, they are shows that have now fallen into local lore as one of the high watermarks— even if misunderstood by some fans— of what makes Athens tick.

As Widespread Panic’s John Bell once recalled in 2012 during a later iteration of the event put together in honor of founding guitarist Michael Houser’s passing in 2002, the point was always to “Get all the musicians— like all the new wavers, and all the art musicians, even the crazy ones— and to get us all together on one stage and have a concert together. Get to know one another. So, it was Mikey’s idea to birth something like this. It was called Bar Tab. And basically there were two things he wanted to be accomplished. Well, three things: make some music. Two: dispel any mystery between all the different genres that were happening in Athens at the time. And so, enough people came through the door to pay for our bar tab. So, this is another installment of Mikey’s vision.”

ERIC CARTER: The one thing I remember about [Bar Tab], and I’m probably going to get some of this wrong, but I think the idea stemmed from a conversation with me and Mikey. Or maybe he kind of had the vague idea for some kind of like mishmash of bands, and came up with that name, so it’s not like “Widespread Panic featuring members of Bloodkin.” We gotta come up with something else. And we’ll just do some covers, and it was a very loose idea initially. And I can’t remember how many of them we did— several of them— and I think the first one went pretty well. And we started building them around, it was either like a medical bill situation or a legal situation. We always kind of turned them into some sort of benefit. And then at some point, it started getting to like, anytime we’re going to say we’re announcing a Bar Tab show— and this might’ve come from Mikey, I’m not a hundred percent sure— it’s like, “Oh, Widespread Panic is gonna play!,” and it just got too much for that place. It was becoming too much of a thing. It’s like, “Oh, it’s a secret Widespread Panic show!” If I’m correct in my hazy memory, I think that’s kind of why it sort of came to a stop, you know? And at that point they were probably going to be out of town more, or some of them may have started to drift to other areas, like moving to other areas. It wasn’t like we were all hanging out together all at the same time. Like, go out to a bar and say, “Oh look, there’s Widespread Panic and Bloodkin sitting at the bar having drinks.” You know? Those things were a lot of fun.

DAVE SCHOOLS: Well, the genesis was a bunch of people getting together because they owed a bunch of money to the bar. I mean, you could ask what’s in a name…(laughs)…but generally it’s Occam’s razor on something like this. Bar Tab started off like “let’s have a party and be able to pay our tab.” But then obviously it got bigger and bigger and it moved into charitable works. You know, I think the die was cast when we did one and we came out and played a new record that we had just made. But then we blew it the next year. This was one of my favorites— I remember our manager, Sam Lanier, had this article from The Red & Black pinned up on the bulletin board in his office— [when] the next year we sold out the Georgia Theatre for a Bar Tab show and it wound up being the brute. record. Like we came out and we didn’t do some Widespread Panic record that was yet to be released— a bunch of new songs. We did this collaborative recording with Vic Chesnutt. And the crowd was just flummoxed. They were stymied. And the article from The Red & Black, it had this little graphic thumbs down kind of thing, and a picture of like JB and Vic on stage, and it just said “Widespread Disappointment.” Of course later the brute. record comes out, and to this day it’s probably still very misunderstood. But I think people have gotten this collaborative thing. But that also speaks to the collaborative spirit, from my side of the coin. And I love terms like ‘collaborative spirit.’ I use it all the time.

DANNY HUTCHENS: You know in those days— Todd Nance and I always talk[ed] about this— the crowds, the fans, it was kind of clique-ish. We always talk[ed] about how Vic Chesnutt was a 40 Watt guy and Panic was a Georgia Theatre band, you know? And those crowds— like the big story about that was, eventually— that Panic and Vic did brute. And leading up to that, we did these Bar Tab shows at the Theatre, which were like all of us, and it was a benefit or a series of benefits. And we all played together, and there were like some bad reviews because it wasn’t a Panic show. Like, “they didn’t play any Widespread Panic!” Stuff like that, which really pissed them off. But there were just people that kind of didn’t get it.

A chronic problem among the public at large when it came to the inner workings of not just the Athens music scene in general, but also the inner workings of Widespread Panic and their extended family and friends, the misunderstanding of just how interconnected all of it is— and always has been— has been a major hurdle that is in some ways still being overcome today. A large network in a small town of artists and artisans bound by music, creativity, and their willingness to support each other and their various projects, in many ways the Bar Tab shows were emblematic of the ethos that has always made the Classic City one of the most revered music towns in all of the country. As a place where people are encouraged by one another to follow their muse, spread their aesthetic wings and take flight, and know that there will always be at least someone in the audience to care about what it is that you’re doing— even if it’s just fellow musicians— and maybe even help it grow and flourish. But more than that, it’s also representative of a spirit of regional hospitality that can largely only be found in the heart of the Deep South, and one that would help define the next several decades of the careers of both Bloodkin and Widespread Panic, as well as David Barbe and newer acts that came to town like the Drive-By Truckers. All of whom would be interconnected and help each other in ways that could only happen in Athens.

LIFER: ON TOUR WITH MOE TUCKER

“I was playing this joint before they were born

I ain’t no civilian ain’t no greenhorn

We stay open from dusk til dawn

I’ll be here singing long after they’re gone”

– Daniel Hutchens, “Lifer”

(Moe Tucker Band, circa mid-1990s, feat. l-r: John Sluggett on drums, Sonny Vincent on guitar, Moe Tucker guitar and vocals, and Daniel Hutchens on bass. Photo courtesy of Sonny Vincent.)

In a town where connections and community were of paramount importance and a guiding principle that has led to not just mutual appreciation and support, but also unexpected collaborations and affiliations, it should come as no surprise that the creative world of Danny Hutchens and Bloodkin extended well beyond Widespread Panic, feral house parties, and venues like the Uptown Lounge and Georgia Theatre. In fact, it would eventually extend all the way into the life and career of one of the most revered and influential groups in all of modern music with the Velvet Underground through the same word of mouth that led people like David Barbe to seek out Hutchens and Carter after first getting wind of their arrival in town back in the mid-1980s. Having earned a reputation around town as a great songwriter and guitar player, at the same time that Bloodkin’s star was beginning to rise with that of Widespread Panic throughout the late-80s and early-90s— although at a decidedly different pace, with Panic quickly jumping out front in terms of popularity due to their persistent touring on both the bar and Southern college fraternity circuit, before graduating to bigger venues— Hutchens would soon find himself in the rarefied company of drummer Moe Tucker, who was in the process of relaunching her solo career with a new band. Having been recommended to Tucker through her daughter Kerry, who lived in Athens and was friends with Hutchens, in a very short span of time he would go from auditioning at her home in Douglas, Georgia, to hopping on a train to New York City with her to play with a band he had never met or rehearsed with before in front of a packed crowd of some of the Big Apple’s most famous rock cognoscenti. Having essentially jumped the line from being a relatively unknown entity from a small Southern college rock scene, to playing with a founding member of the Velvets, Hutchens would not just stick the landing and become a beloved touring member of her group throughout the early-to- mid-1990s, he would eventually wind up as a guitar tech on the Velvets’ 1993 reunion tour, overseeing sold out concerts all over Europe and hanging out with the likes of Lou Reed, John Cale, and another member he would grow extremely close to through his time in Moe’s solo band and with the Velvets, Sterling Morrison.

But that would come a little later. First, he had to prove himself in the crucible of the downtown New York art rock scene by being thrown off the deep end during one of the most taxing gigs he would ever play as a professional musician. It would also be his introduction into working with a coterie of underground rock musicians whose pedigrees would reach back into the earliest days of the New York City punk explosion at CBGBs and Max’s Kansas City, in the form of veteran guitarist Sonny Vincent from Testors, as well as a nexus of newer indie rock bands like Half Japanese, through drummer John Sluggett, and acts like the B.A.L.L. and Violent Femmes. All of whom were a far cry from the rootsier sonic world of Widespread Panic, yet also very much related in terms of the larger independent rock scenes developing all over the country throughout the 1980s, and playing music that Hutchens was very much a fan of going back to his admiration of people like Patti Smith and the Ramones. Unknowingly connecting disparate sounds and scenes from across the United States, Hutchens would ultimately make his mark on all of them along the way, and all thanks to Moe Tucker taking a chance on a hungry young upstart from West Virginia who was looking for opportunities to spread his wings and prove himself among some of rock’s heaviest and influential hitters. The beginning of a journey that would take him around the world long before he ever really toured with Bloodkin, it was an experience that would shape his ideas and attitude toward art, fame and the music business in deep and profound ways.

DANNY HUTCHENS: Moe had started playing music again before I met her. After the Velvet Underground she had had stopped playing music. She was working at a Walmart in Douglas, Georgia. She started playing music again and made a record before I met her [1989’s Life In Exile After Abdication, which featured contributions from members of the Velvet Underground, Half Japanese, and Sonic Youth], but she had this show coming up in New York City that somehow she had booked. It was kind of like a big New York City deal, Lou Reed was coming and all this stuff, and she didn’t have a band. She was auditioning people to put a band together for this one show [*]. And so I guess she kind of gave her daughter the mission of like scouting out musicians in Athens, Georgia, you know? And I knew her— I knew Kerry— and she recommended me. And I went down to Douglas and tried out and I got the gig and I actually played guitar for that show. \\ Man, looking back, it was like this big deal, New York City kind of— you know, the kind of shit that I’m like, how did I wind up here? It was a big deal. Everybody was there— like the New York arts and music community was there. This was like Moe’s coming out party. And it was just a blower to tell you the truth. That show, I have such vague memories of it. I just remember busting my ass to all the songs just not to let her down. I don’t even remember everybody to tell you the truth. Like, I practiced with Moe down here, and we went to New York. It was just crazy. We rode the train to New York and back, and I remember talking to Moe on the way back— you know, this was when she was starting to actually think about playing music full-time or professionally again— and we hit it off, is what it comes down to. I mean, just as people, you know? I really liked her. She was just a very nice woman. And I respected her music. I really liked it. The Velvets, but also the stuff she was getting into as a solo artist. [*- Tucker had actually been touring for several years with a band, and had released several albums, EPs and singles as well going back to the early-1980s, but was recruiting new members to play on upcoming tours and releases.]

SONNY VINCENT (from Moe Tucker Band/Testors): It was a really cool show. I had been playing with Moe for a while, so I didn’t have the same kind of like sink or swim feeling that Daniel had. But, it was great because there were people from the Factory there, and Legs McNeil was there, and it was really like a lot of celebrities and a lot of friends. Some people I’d met before. When I was a kid I did spend some time in Andy Warhol’s Factory and met some people, so it was really kind of a cool thing for Moe and for us. And I guess it was terrifying for Daniel. Probably would have been good to build up to something like that instead of jumping right in. \\ I remember that before Daniel we had different people that just didn’t work out— Moe didn’t like them. Oftentimes her young daughter, who I guess was still in high school, was recruiting musicians from the local area and saying, “Hey mom, you know you should check this guy out,” and then she would and we’d bring them on tour, and it would be some kind of catastrophe ‘cause Moe didn’t like them. So this one was kind of like bingo— like great. So when Danny showed up we were all happy. He was personable, he was nice looking and was polite, and just a really easy going guy that we felt we could be crammed in a van [with] driving all day.